AQUIND Interconnector is a subsea cable that would link the French and British electrical grids, enabling excess power generated on either side of the English channel to flow wherever there is excess demand. When completed the interconnector would transmit 16 TWh yearly—equivalent to 5% of the UK’s annual electricity consumption.

The cable would connect the Barnabos substation in Normandy with the Lovedean substation in Hampshire, but there would be significant sections of subterranean cabling on both sides. In England, the cable would come ashore at Portsmouth and run 25km to Lovedean; in France, it would run 40km from Le Havre to Barnabos.1 The proposal has been met with determined protest from locals in both countries.

On 30 July 2018, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) announced that the AQUIND Interconnector would be treated as a Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project (NSIP).2 This meant the proposal would get to bypass normal planning requirements, cutting the local government in affected areas out of the process (in this instance: Portsmouth City and Hampshire County Councils).

The project would not normally have qualified, but the then Secretary of State for BEIS, Greg Clark, used his discretion under Section 35 of the 2008 Planning Act to grant AQUIND’s proposal NSIP status.3 As a consequence, the planning application would be overseen by the Planning Inspectorate, who would give a recommendation to the relevant Secretary of State, who in turn would make the ultimate decision.

On the same day the Department for BEIS made the NSIP announcement, the governing Conservative party accepted a £12,000 donation from Alexander Temerko, one of AQUIND’s directors.4 At that time AQUIND’s ownership was hidden through an offshore shell company registered in the British Virgin Islands, but earlier this year Temerko was revealed as AQUIND’s 50:50 co-owner.5

Kwasi Kwarteng was appointed the new Secretary of State for BEIS in January this year; the third since Greg Clark. His predecessor Alok Sharma had to recuse himself from the AQUIND decision last April, due to fears of a potential conflict of interest. Two months earlier he had shared a table with Alexander Temerko and his fellow AQUIND director, Kirill Glukhovskoy, at the Tories’ annual Black and White Ball fundraiser. The company paid £12,000 for the table, having donated another £10,000 to Sharma’s constituency of Reading West only a few months earlier.6

A month before Sharma’s self-recusal, Kwarteng—who was then the Minister of State for Business, Energy and Clean Growth—wrote to Temerko about the AQUIND Interconnector, saying:7

“I do not think there is much doubt that the UK government and Ofgem support the project.”

Another current minister in the Department for BEIS is Lord Callanan, who was a director of AQUIND for more than a year until June 2017.

Last week the Planning Inspectorate gave its recommendation report to the Secretary of State for BEIS; Kwarteng now has until 8 September to make his final decision.

Given the amount of power over Britain this project would give to AQUIND—both literal and figurative—it’s imperative the government knows who will be financing it.

For more than 10 years, and until very recently, the ownership of AQUIND (and before it: the OGN Group) was hidden through a series of offshore shell companies. Nevertheless, within the companies’ ownership changes lie clues to its sources of funding. As the deadline for that planning decision approaches, let’s take a close look back over the business journey that has led to this moment.

Part 1: Temerko and Ms Love—an odd pair

In part 1 we start by looking at SLP Engineering (SLPE), the manufacturing company in East Anglia that built offshore oil platforms for more than 40 years. AQUIND is a direct descendant of that business.

We look at some of the events leading up to December 2005, when Alexander Temerko was spared extradition to Russia, in a case that “bolstered his standing as a Russian dissident who’d suffered at the hands of the Russian state, helping secure his footing as a donor who could be trusted”.

The following December, Temerko hosted a drinks party at Kensington Palace, under the auspices of Prince Michael of Kent—the Queen’s “unofficial ambassador” to Russia—followed by dinner at the exclusive Mark’s Club. The evening was attended mainly by “a mixture of art historians and Russian businessmen”, including a trio who would later join Temerko on the board of SLPE.

In 2007, Temerko was made a director of SLPE, where he joined fellow soviet-born board member Lubov Golubeva. The following month a BVI-registered shell company, OGN Investment Partners, acquired a 46.5% stake in SLPE.

We examine some of Golubeva’s prior employment, which contrasts with Temerko’s in such a way that their (very short) boardroom concurrence raises eyebrows.

Golubeva left SLPE shortly afterwards and later that year she married the former Russian deputy finance minister, Vladimir Chernukhin. In the decade-plus since, Lubov Chernukhin has donated more than £1.8 million to the Conservative party, making her “the biggest female Tory donor in British history”.

Chernukhin had also been a director of Rockpoint Investments: the holding company OGN Investment Partners bought to acquire the 46.5% stake in SLPE. Therefore I argue that her path crossing with Temerko’s—precisely when the takeover of SLPE began—was more significant than the coincidence it has been treated as by most media reports to date.

Part 2: Three oilmen and an accountant

Part 2 begins with a look at a quartet that shared the SLPE boardroom for precisely one week in July 2008, 18 months after the party at Kensington Palace that all four attended.

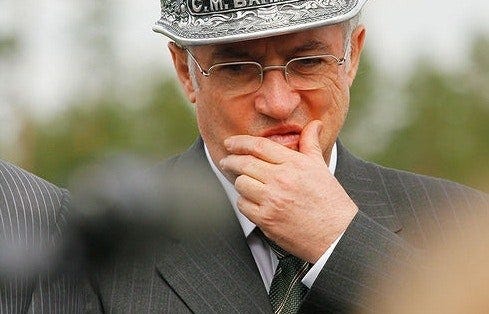

Alexander Temerko, 54, was born in the Ukrainian SSR but has had British citizenship since 2011. He spent most of the 90s working for the Russian government, as a trusted member of Boris Yeltsin’s circle.

He worked several senior roles in and around the Ministry of Defence; helped to establish a state company that exported weapons, Voentech; and acted as the founding president of another, Russian Weapon.

He then spent 5 years as an executive at the private Russian oil company YUKOS, primarily tasked with using his government contacts to “strengthen [their] relationship with the federal authorities”.

Richard Glasspool, 65, is a chartered accountant from Southampton with more than two decades’ experience working in and around Russia.

He has been working alongside Temerko since at least February 2007, when the Russian émigré first joined the board of SLPE.

Semyon Vainshtok, 73, was born in the Belarusian SSR and spent most of his childhood in the Moldavian SSR. He spent all of the 90s working as a senior executive at major oil companies, most of it as a vice-president of Russia’s biggest oil company, LUKOIL.

In 1999, he became one of the most powerful businessmen in Russia, when he was made president of Transneft, the Russian state’s oil pipeline monopoly. He held that role for eight years, the last few of which were spent working on the East Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline.

He was then appointed by Vladimir Putin to oversee the Russian state’s preparations for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. He resigned from that position after just seven months, left for London, and only a month later was appointed to the SLPE board.

Soon after Vainshtok’s arrival in the UK, the Russian Accounts Chamber began investigating allegations of widespread contract fraud and embezzlement during the ESPO pipeline construction, under his watch.

Vainshtok was only a director of SLPE for a few months and there is nothing to suggest he is still involved with the group, but just three days after his appointment in May 2008, OGN Investment Partners increased its ownership from 46.5% to 95%.

Viktor Fedotov, 73, was born in Ufa, Russian SFSR. He worked alongside Vainshtok at LUKOIL, where he was a vice-president from 1990-98. Then from 1998-2001 he was the head of the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC).

Fedotov kept a very low profile in Russia, despite having occupied a number of senior executive roles in the oil industry for more than a decade. I previously uncovered how, from 2003-07, he had been the chairman of two companies that were awarded contracts on the ESPO pipeline project. Those companies—VNIIST and IP Network—were alleged to have embezzled billions of rubles (more than £80 million combined) from the Russian state, via Vainshtok’s Transneft. Amazingly, Fedotov’s name had never previously been mentioned in connection with the ESPO corruption allegations.8

Part two concludes with an explanation of how SLPE was forced into administration in 2009, when it was sued by a client amid the global recession, in combination with an unprecedented collapse in oil prices.

Part 3: AQUIND ready to set sail (at last?)

Part 3 looks at how a new group of companies was launched from the ruins of the old. The Offshore Group Newcastle (OGN) Group of companies—of which Aquind is one—started trading in 2010. The operation was relocated from the old SLP base in Lowestoft, up to a shipyard in Wallsend, a few miles east of Newcastle along the River Tyne.

For five years, the OGN Group was a very successful business, but it met the same fate as the SLP Group before it, after the price of oil crashed again in 2014. Aquind was cast off from the OGN Group prior to the other companies winding up, but it appears to have been ‘bought’ by the same offshore owners that sold it.

The series concludes by answering the question, as it pertains to today: Who owns AQUIND? [Note: I have appended details of new developments since part 3 was first published.]

Did you enjoy reading this?

I have been investigating AQUIND and its owners for three years now, and I have an abundance of exclusive findings that have never been published elsewhere. If you’ve you’ve enjoyed reading this then I would encourage you to subscribe to HyperFocus: the home of ADHD-fuelled investigations into a broad range of subjects—including a series dedicated to AQUIND. Any future work will be sent straight to your email.

AQUIND Limited. 2020. Request for Exemption: AQUIND Interconnector. Available at: <https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/ofgem-publications/169743> [Accessed 18 June 2021].

AQUIND consultation. 2018. AQUIND Interconnector to be considered as a Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project. [online] Available at: <https://aquindconsultation.co.uk/aquind-interconnector-to-be-considered-as-a-nationally-significant-infrastructure-project/> [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Environment Analyst UK. 2018. French-UK interconnector to go through DCO process. [online] Available at: <https://environment-analyst.com/uk/69214/french-uk-interconnector-to-go-through-dco-process> [Accessed 17 June 2021].

The Electoral Commission. n.d. Donation C0399773. [online] Available at: <http://search.electoralcommission.org.uk/English/Donations/C0399773> [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Elliot, P., 2021. AQUIND owner is no longer 'anonymous'. [online] HyperFocus. Available at: <https://investigations.substack.com/p/aquind-owner-anonymous-no-more> [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Smith, M., 2020. Tory Energy Secretary dined with donors behind £1.2bn pipeline at fundraiser. [online] Mirror. Available at: <https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/politics/tory-energy-secretary-dined-donors-22349093> [Accessed 17 June 2021].

Greenwood, G. and Midolo, E., 2021. Kwasi Kwarteng voiced support for Channel power link after Tory donor’s lobbying. [online] Times. Available at: <https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/kwasi-kwarteng-voiced-support-for-channel-power-link-after-tory-donors-lobbying-rfn5hldqm> [Accessed 15 June 2021].

Elliot, P. and Wild, F., 2021. Owner of Tory donor company chaired firm linked to Russian corruption allegations. [online] The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Available at: <https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2021-01-12/owner-of-tory-donor-company-chaired-firm-linked-to-russian-corruption-allegations> [Accessed 18 June 2021].

Hi Paddy,

I'm a postgraduate student in Photojournalism at London College of Communication, working on a collabortation project with STOP AQUIND group to make a zine about the aquind issue and campaign.

May I use the picture you made in this article? The project is only for academic use and won't be used in any commercial way.

If you would like to learn more please contact me @linziqi1056996415@gmail.com